Cycling in Peru soon teaches you one thing: that the scale of this country’s landscapes is immense. So vast. So huge. A country so vertical that local people can’t even see a 1000m ascent. A climb bigger than England’s highest mountain is so insignificant as to not register.

We often ponder as we’re cycling down and up Peruvian hills, what we’ll feel when we’re back pedalling in Europe. Will we be hard to impress? Or does scale not really matter?

These days we’re already thinking and acting a bit Peruano. Six months in a country does that to you. We’ve started discounting paved passes as not being ‘real’ climbs. They require far less effort, and so are, comparatively speaking, ‘flat’. We hunch over our menu soups, left elbows on table, face low to bowl. And why not? We spill less that way. We scrutinize bank notes to check for fakes. We enjoy extending our de freeeeentes (‘straight on’), and elicit giggles from locals by adding -pe to the end of sentences.

A foreign country has never felt so much like home.

As we neared the end of our route from Huaraz to Abancay the sheer variety of landscapes in this memorable month continued to surprise. From the gaping, arid, cactus-filled gorge at Cañon; to the high altitude Puna; the hundreds of lakes; the multi-coloured hills; the weird rock formations; the unparalled Rio Cañete; the bottomless Rio Pampas valley; right up to our final day of escarpments and plateaus near Chicha.

But throughout all this scenic flux, two things remained a constant. The warmth and friendliness of the campesinos. And the switchbacks.

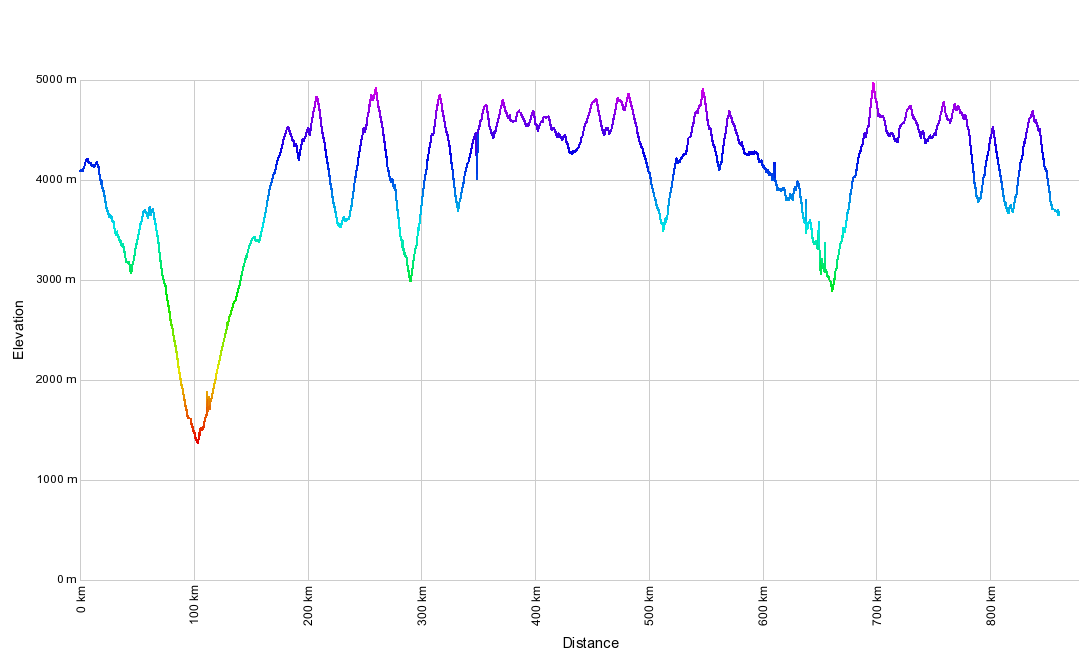

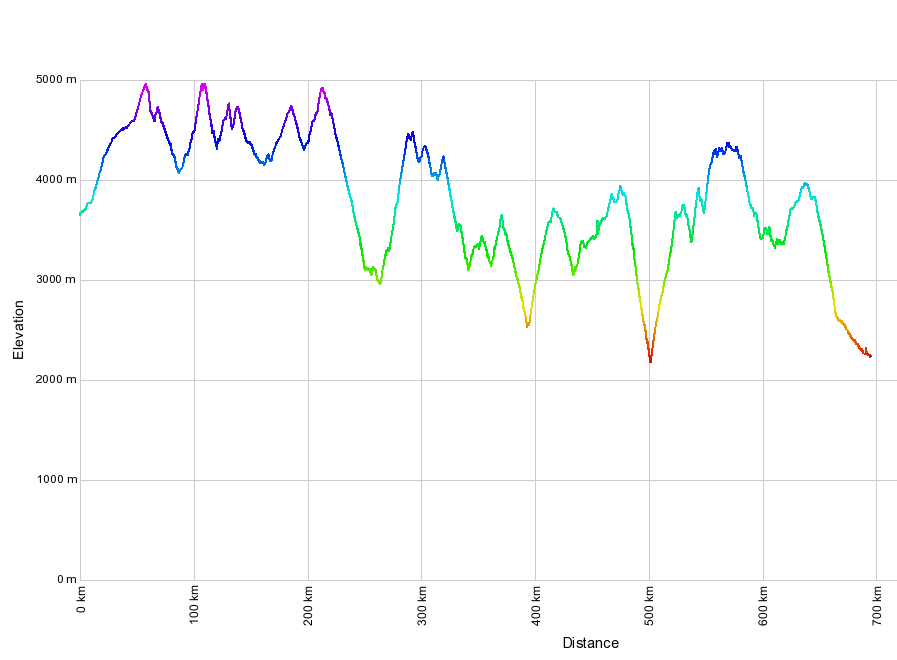

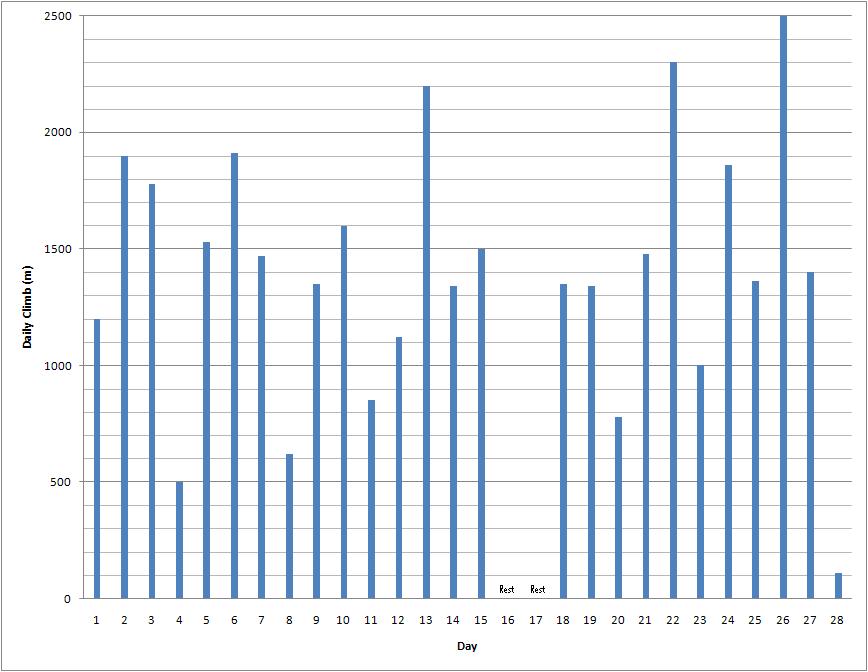

Four weeks and 1580km after setting out from Huaraz we jumped on a bus near Abancay. In that time we’d climbed over 36,000m, and descended over 38,000m. An Everest A Week. Some locals may think their country only has subiditas*. We thought them subidazos*. It was time for a rest.

(* The diminutive and augmentative of subida (climb).)

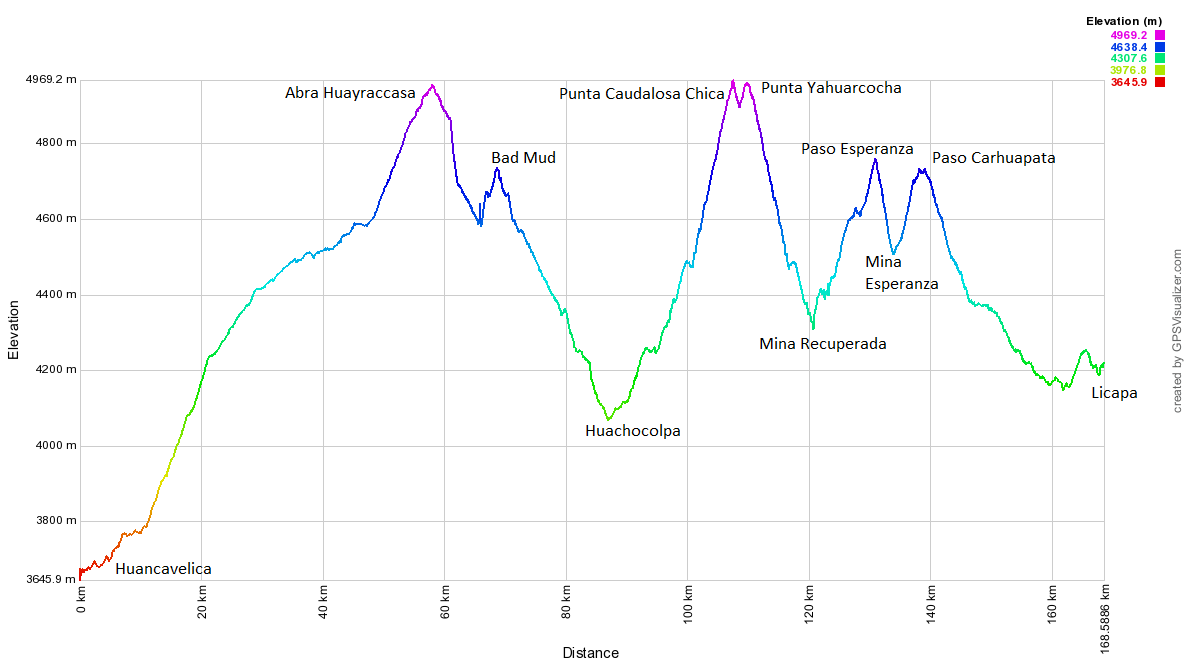

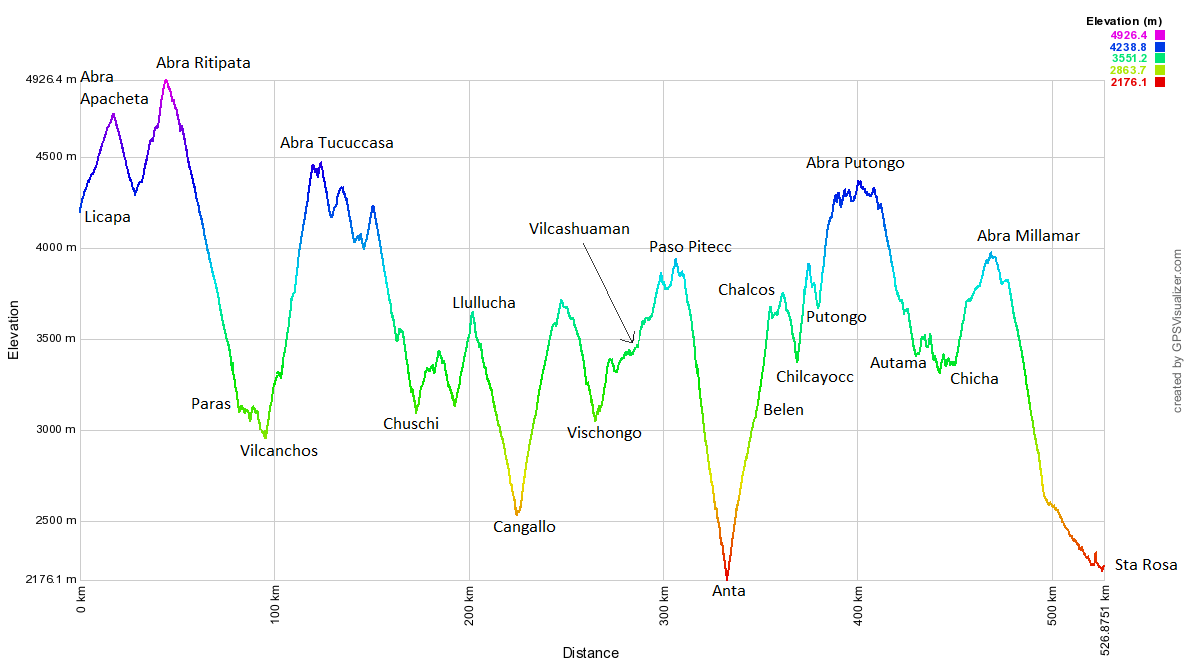

Elevation Profile

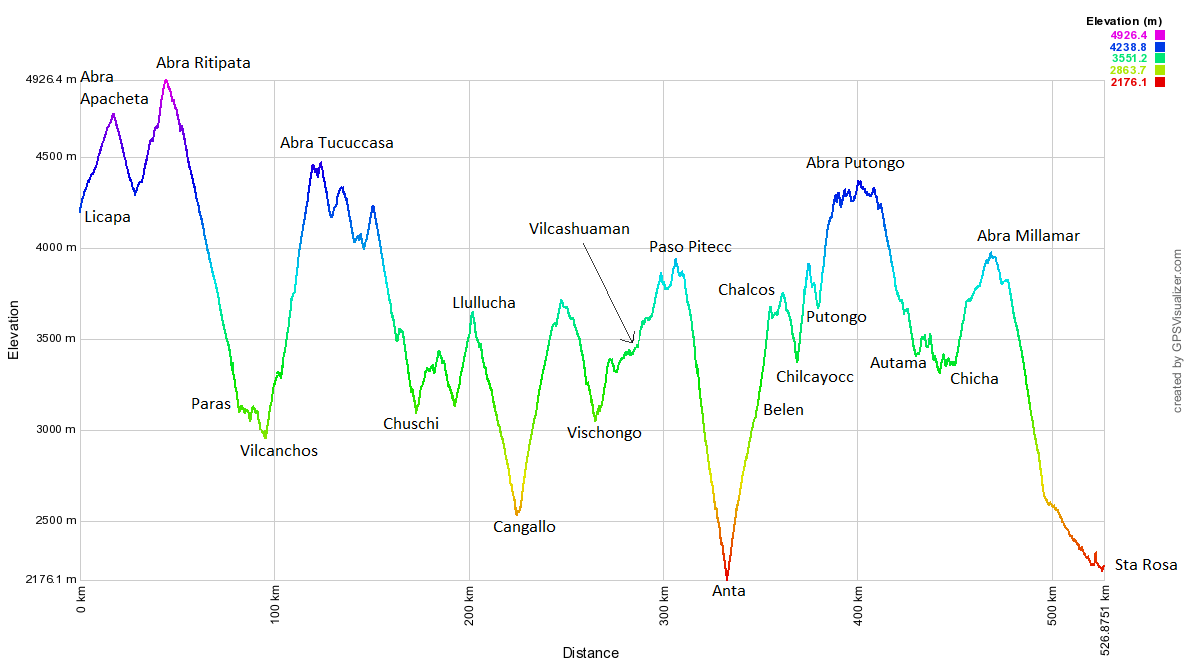

Stats – Licapa to Santa Rosa

8 days

539km (83km paved)

12,000m climbed

6 x 4000m passes

12 Chocolate bars, 600g of pasta, 6l of pop each (being in villages means less pasta and more pop and cakes – hooray!).

After turning off the paved Libertadores highway to Ayacucho, there’s a 2 hour climb to Abra Ritipata, which, for a change, features few hairpins. So we see less of the yellow and black unofficial National Emblem of Peru. There are still a couple of zigzags though, of course.

A sign! A sign! Imagine our excitement at finding this beauty. It means we don’t have to make up a name for the pass, or find a local person to make up a name for us. Our GPS reads 4950m.

- We’d been looking forward to the descent from the pass to Paras for ages. On Google Earth it looks like this.

But to our great disappointment, on the day, the weather looks like this. Still, there are some colourful hills around.

But it’s a damp afternoon, with mist and cloud in all directions. The 30+ hairpin descent is miserably wet.

Once down in the valley depths, the sun comes out and we meet this work gang near Vilcanchos. In the villages, all the residents are required to give up time for community works.

Here’s a more solitary, pensive member of the team.

The following day we head from Vilcanchos to Chuschi. It’s only 20km in a straight line, but there’s no road the whole way along the valley. One is being built however, and we’re tempted to bike-hike when some of the locals say there’s only a small section missing. Then there are mutterings about it being a 2 hour walk, and a subidazo at that, so instead we opt for the long way round by road. It turns into a mammoth 80km day.

An hour into the climb we chat for a while to this nice gent in Veracruz. Seeing as we’re now half Peruvian, we shake his, and half the village’s hand. A soft shake of course; no bone crushing occurs here.

Then, four hours into the climb on what amounts to a very steep farm track, the rain arrives. These are the offending clouds. The subsequent 2 hours are the most triste (sad) of our whole ride. We make it to the 4500m pass at noon. It’s 2C, and we’re wet to the core.

5km into the descent is the small village of Tuco. We’re looking a bit pathetic, and feeling it too. We hang around, hoping someone might invite us in for a cup of warming tea. To our delight, this girl’s dad obliges, and for this we’ll always be grateful. We continue, with a warm cinammon glow inside. The colourful hat is typical of Chuschi – all the women, and some of the men, wear it round town.

In the late afternoon the sun comes out, so we can enjoy the long descent to Chuschi.

But by now it’s getting late. This is the impressive Rio Pampas valley at dusk. We arrive in Chuschi well after dark, 13 hours after leaving Vilcanchos. Knackered after 9 hours of pedalling and 2300m of climbing, we head straight to bed in the Municipal Hostel.

The next day we decide to take it easy, and have a short day to Cangallo. We’re surprised to come across a paved road, but then Neil’s GPS leads us onto a small, barely used 4×4 track. It turns into a great shortcut to town.

We pace it down to the provincial capital…the thunder has started early, and we don’t fancy another drenching.

Where would we be without Google Earth? This track didn’t appear even on the Ministry of Transport maps, and it looked so small when we first joined it, that without having viewed satellite photos we’d never have thought about venturing onto it.

Cangallo turns out to be a town full of murals…

…and curious kids full of stories about everything that’s wrong with their bikes.

It’s Señor de los Milagros day, so we join the hordes processing around the Plaza. A ghostly bici crosses the flower-petal covered streets.

The next day sees us climbing again, away from the Rio Pampas and over to Vilcashuaman.

We pass some school adverts in Putica – a common site in Peru.

And in the same village meet Carlos, a proud father of nine. ‘What do you mean most people only have 2 or 3 kids in England? Do you need me to fly over there and boost productivty?!’ The local shopkeeper overhears and seems unimpressed. ‘You’ve got enough already! You can’t even keep your current brood properly fed!’ We sidle away…

And pass through colourful hills on the way to the important Inca centre at Vilcashuaman.

In their usual tactful way, the Spanish knock down the Sun Temple, and replace it with a church. But it’s nice enough to look at, and seems well used by the current populace.

The wall-building competition isn’t even remotely competitive. Incas 1, Spanish 0.

The Plaza is large, though not nearly as big as in Inca times. Despite featuring briefly in the Lonely Planet, our reception tells us this place receives few tourists. It’s of the ‘shake hands with everyone’ kind, rather than the ‘get pounced on by touts’ Cusco sort.

On a wander round town we observe some typical Peruvian street scenes. Animals share the streets with old bangers and 4x4s.

As we’re leaving our hostel the next morning, the owner asks us where we’re headed. ‘To Saurama, then Andahuaylas’, we reply. ‘But how will you cross the Rio Pampas? There’s no bridge.’ Which explains why we couldn’t see one on the satellite pictures. We spend the next 2 hours going round town, asking about alternative routes to Abancay. The municipality workers are helpful, as are the taxi drivers. We end up with 2 options: head back north for a day to meet the main paved road, then follow this 3 days to Abancay. Or head south on small roads, which apparently lead to the town of Querobamba, and from there make it to the Nazca-Abancay paving.

We opt for the latter, despite warnings that we’ll ‘sudar mucho’ (sweat buckets) on the climb up from the Rio Pampas at Anta. For the hundredth time a Peruvian exhales slowly and draws us ‘air switchbacks’. If he’s right, the climb up from the river is interminable.

The 1700m descent down to the river seems interminable too. It’s on an awful surface, which would’ve seen us regularly pushing, had we been unfortunate enough to be going in the opposite direction. But at least sections of the road and surrounding rocks are purple – such a deep shade of it, such as we’ve not seen before.

After a few hours descending we near the bridge. The sign says it’s closed, and there are others saying it’s pedestrian only, but this doesn’t stop the occasional 4×4 sneaking over. The ‘air switchbacks’ manifest into reality. There are over 30 of them.

The crossing’s a bit wobbly on a bike. We hate to think what it’s like in a vehicle, but as this is the only way over this huge river for tens and tens of kilometres, some drivers feel they have little choice but to use it.

After overnighting in the 5-family village of Socos, where we’re put up in the village hall, we continue climbing. To our delight, for the umpteenth time this journey a descent on a bad surface leads into a climb on a good one. From the river at 2200m we can pedal the whole route, and don’t stop climbing until we’re at 3700m.

The suspension bridge begins to look smaller and smaller as we wend our way up the zigzags…

…and after a few hours we make it to Chilcayocc to hang out with a load of chicas. People have told us the climb above town is a tough one, and they’re right. For the third time since leaving Huaraz our route climbs over 400m in 4km.

We make it to Putongo, then climb again. As we no longer have GPS information we’re having to stop at every junction and town, to ask in-the-know locals about which roads to take. This leads to an excellent shortcut, over a 4400m pass, to Soras, thus avoiding the descent to Querobamba. The next day we make it to Chicha, then climb once more to Sañayca. The scenery changes again – this day it’s all escarpments and plateaus.

Night overtakes us before reaching Sañayca, so we set up one last Peruvian camp. As has become our custom we don’t bother straying far from the road – we’re pretty sure, having only seen one vehicle all afternoon, that there’ll be no traffic passing in the night.

Our last Peruvian sunset is one to savour and remember. The next day it’s a 1000m descent to the paving, and we pedal downhill on this for 30km to Santa Rosa. In 2010 our route took us from Tierra del Fuego to Santa Rosa, so having linked up the journeys we jump on a minibus to Abancay, then a bus to Cusco. These 6 hours remind us why we no longer backpack. The minibus is nearly hit by a landslide (ok, so this would’ve been far worse on a bike), then the kid in front of us pukes, and as the window is open flecks of vomit fly in our faces and hair (this has yet to happen to us while biking). Then, on the bus to Cusco we come perilously close to being pushed into a river by a juggernaut coming at speed round a blind bend…

Acknowledgements: We’d like to thank the Peruvian Ministry of Transport and Communications for making this trip possible, through the building of such an excellent network of unpaved, unused mountain roads. If the Indian Prime Minister should ever read this, we suggest, Sir (Your Highness?), that you fly some Peruvian engineers over to the Himalaya to teach the Border Roads Organization et al how it’s done.

[flickr_set id="72157637393149655"]