When heading out on rarely used dirt roads we’ve been asked a few times if we’re not afraid of ‘El Silencio’. That haunted silence which reigns in Peru’s wonderful mountain wildernesses. It’s hard for Peruvian campesinos to understand that it’s El Silencio that we’re here for. Where we come from it’s oh soo hard to find.

What we are afraid of is ‘El Sonido‘ (the Sound) – that rumbling of thunder which usually begins around 14:00 and has plagued both our Peruvian cycling trips. (Yes, we know it’s our own fault for being here in October again…). It was the reason we curtailed our last trip in this stunning country in 2010, when the terrifying lightning storms made us turn around at Abancay. This year our visas run out too soon to enable us to reach Bolivia by pedalling alone, so we’ll bus from Abancay. For those looking for dirt road adventures, 6 months is nowhere near long enough to explore Peru’s myriad of remote cycling opportunities.

Plus, the storms are here again. Fortunately not as powerful as 3 years ago, but they’ve still put an early end to many of our cycling days. As blue skies suddenly give way to towering cumulonimbus and the flashes begin, rubbish camps have become somewhat habitual. Though puddles and muddy roads are becoming all too frequent, ironically a lack of water sources has recently led to some slightly tainted cups of coffee and aniseed tea. After Punta Pumacocha we were left drinking from a scummy pond when the roaring arrived; the following day Neil was to be found syphoning ditch water from a muddy hairpin bend…

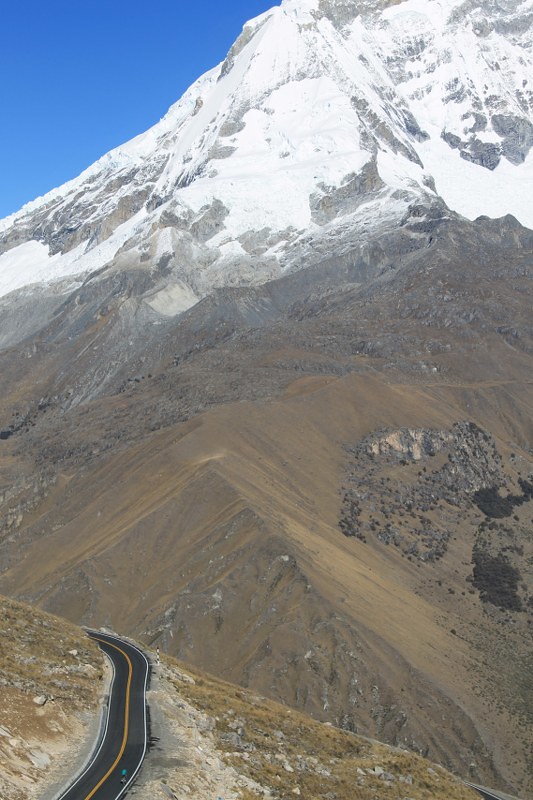

But the riding in between is more than making up for these minor inconveniences. And how. Our vertical route down Peru surpasses in beauty almost any other route we’ve ever taken.

After 6 days, and a few tough, tough climbs, we made it from the Carretera Central to Huancavelica. This pleasant provincial capital had been a milestone in our ride for a while. Each night in the tent we’d work our how many passes still separated us from ‘Old Huanky’; horizontal kilometres didn’t seem to mean so much any more.

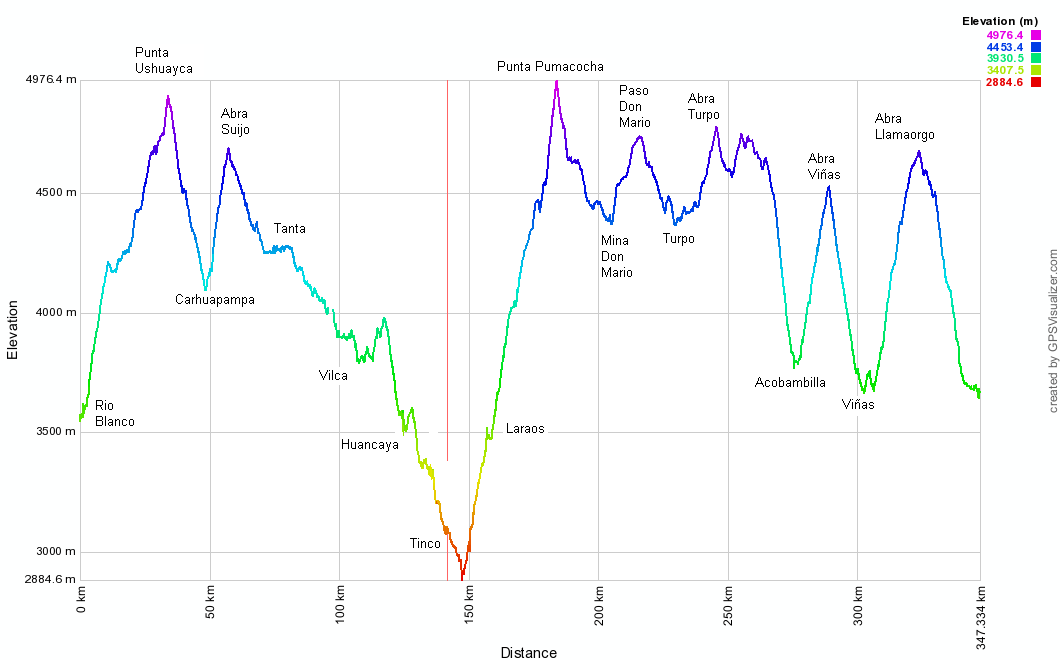

Elevation Profile

Stats – Carretera Central to Huancavelica

6 days

354km (23km paved)

8,700m climbed

7 x 4000m passes

12 Chocolate bars, 950g of pasta, 4.5l of pop each.

After leaving the traffic madness on the Carretera Central, we camp at a fish farm. It’s one of hundreds in these parts – most lakes have a trout farm – and the freshly caught fish is a delicious treat. In the morning comes the long climb to 4930m Punta Ushuayca. It’s a lovely quiet road, and we’re left to weave all over it as we please. Which is just as we like it.

Nearing Punta Ushuayca the road steepens and the surface goes a bit muddy. Here’s a haggard looking Neil…

At the top of the pass we meet the day’s second and last vehicle; a truck headed for Tanta. As we take photos it descends, but we soon catch it on the first hairpin. Rather than turning the corner, it has slid down it, and the front left wheel is perilously close to going over the edge. Some careful rock placement and desperate reversing later it makes the turn, only to repeat the performance a few more times before reaching the valley floor.

The descent from Punta Ushuayca immediately turns into the climb to Punta Suija. Though this is a short one at just 500m, the surface is bad and requires full concentration. Haz manages to force her way pedalling to the top, while Pike’s combination of no weight at the front of his bike, and inherited poor balance means he’s left pushing some short sections. Still, as this is the only pushing required on the roads between Huaraz and Huancavelica we’re quite satisfied; we’d readied ourselves for more.

Nearer the top of Punta Suija the terrain eases and we’re able to look around at all the lakes and snowy peaks (out of shot to Neil’s left) on show.

The descent from the pass is on a beautiful road which leads to Tanta. On the way a 10m climb breaks us and we realise we’ve gone way into the red. A stop to eat all our remaining chocolate puts things to right.

After Tanta, Google Earth shows its good and bad sides. The town we’re heading for is labelled as ‘Carhuamachay’ on GE, but our requests for directions to this place draw blank looks. But we know what the village looks like – it’s at the end of a lake, by some pretty waterfalls. ‘Oh, you mean Vilca?’ And yes, we do. But, more importantly, GE marks a road from near Tanta, along the Rio Cañete straight to Vilca. Looking closely at the satellite photos revealed this doesn’t actually exist…

…but it does give us the idea to try and bike-hike the route, avoiding a 50km detour over two passes. Usually we wouldn’t shun the possibility of going over a few high passes, but this bike-hike is just too tempting.

Particularly when you get the opportunity to become troglodytes for the night. Another thing ticked off our ‘To do’ lists. We took refuge in this well-kept cave at 16:00 when a thunderstorm arrived. By 18:00 it was still going, so we pulled out our sleeping bags onto the nice insulating hay.

The sun was out (as usual) in the morning, and we are delighted to find much of the chaquinani to Vilca is rideable.

The shortcut saves us a day’s riding, and Vilca is indeed as idyllic a spot as GE had implied. With an old Colonial bridge to boot, the road from town leads down the Rio Cañete valley…

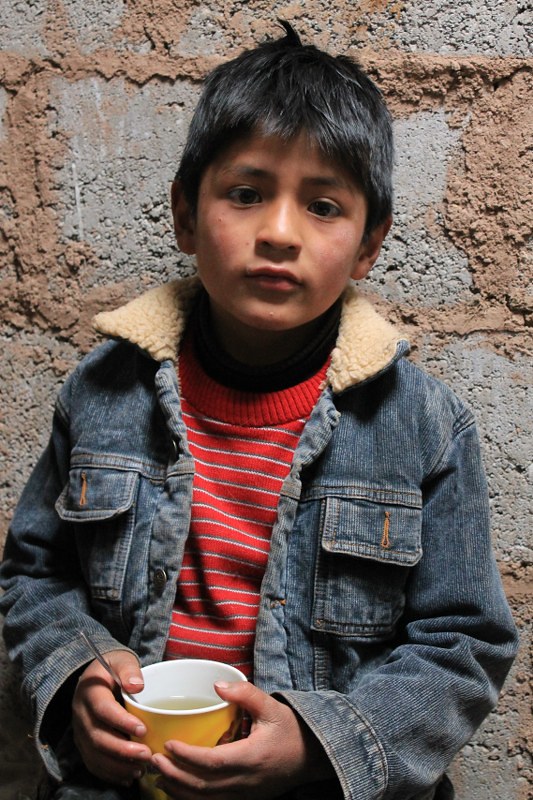

Rather than a bog-standard river, it turns out to be a series of sapphire lakes, punctuated by waterfalls. Sport Ancash’s biggest fan scoffs some snacks while taking it all in.

We’d never heard of the valley, but it’s known to Limeños – a couple of the villages lower down have numerous accommodation options. It’s easily accessed from the coast on a (mostly) paved road.

The day we wrote this post we were sent an email from the Lonely Planet about the most beautiful landscapes in the world. One of them was Plitvice Lakes in Croatia, which in photos look just like Rio Cañete, only on a much smaller scale. Wikipedia says the Croatian lakes span 7km and drop 130m. We’d estimate these ones dropped about 200m over 12-15km.

After dragging ourselves away from the cruise down the Rio Cañete, a downpour drenches us on the climb to Laraos. We stay in the municipal guesthouse then set off at 05:45 the next morning, hoping to beat the bad afternoon weather to the top of Punta Pumacocha.

It’s a spectacular climb, but near the top becomes savagely steep. Here’s Haz despairing when the pass comes into view (it’s the L of the two low points on the ridge). Only 2km away in a straight line, it’s still 450m above us – the most intimidating looking pass we’ve ever seen.

But the surface has been recently ‘cleaned’, and to our amazement it’s all rideable. At 4600m my cycle computer registers a gradient of 23% – the steepest it’s ever given in 4 years of ownership. Neil plays hare, pedalling hard for a few hundred metres then resting. Haz’s impressively slow tortoise pace sees her crawl up at 3.5kph.

At noon, and after 6 hours of climbing we reach Punta Pumacocha. Our GPS says we’re at 4990m – 40m higher than the reading on Google Earth, but then the gradient on the north side is near vertical.

It’s a relief to have made it to the pass; the top 4km are at an AVERAGE gradient of 10.5%! Not the easiest thing to climb when you’re at nearly 5000m…

The south side isn’t nearly as steep, but the surface is pretty awful until we reach this lake and have some lunch. Then comes a flattish section to Mina Don Mario. Fortunately there’s no one around there, so we sneak through the mine and climb to the next pass.

Then comes a lovely section of road. The Peruvians seem pretty expert at building great roads which are never used. We love them for this.

Then the next morning…Doh! Good job we’re carrying that roll of duct tape from Huaraz. Supported by a webbing strap, Haz is able to get her pannier to a cobbler in Huancavelica.

A couple of easy passes sees us through Acobambilla and into Viñas. We have breakfast with this cheery pair in a shop, then I ask to take a photo before we continue. 30 mins later the lady on the L has finished combing and plaiting her hair, and is ready to be snapped. Some people!

The inevitable ‘it’s flat’ comments are muttered by a few in Viñas, but it’s a 1000m climb to Abra Llamaorgo. On the way my cycle computer records a 24% gradient… A few water purifying rests in the ‘pannier arm-chair’ are called for. Note duct tape.

At Laguna Tanserecocha we chat to Alejandro, who questions us about England, then asks which counrties are nearby. ‘France, Holland, Spain’, we answer, ‘but Europe is small so everywhere is close by.’ ‘If it’s so small,’ he replies, ‘why does it try and dominate the whole world?’ We ponder this as we continue to climb.

…then after crossing Abra Llamaorgo comes the fast descent to town. To our delight, the road surface – from the moment we enter the Department of Huancavelica, to reaching the town itself 2 days later – is absolutely perfect.

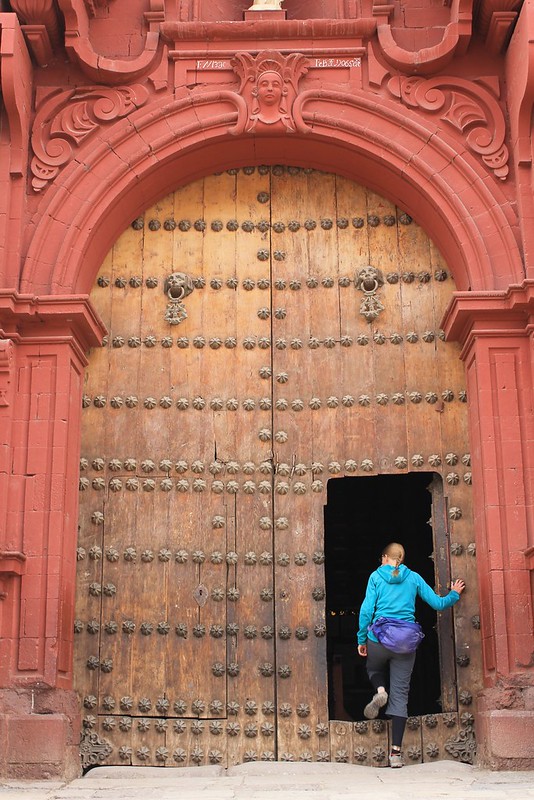

15 continuous days of cycling and we arrive in Huancavelica. It’s small for a departmental capital, and is a charming place. Lots of old buildings around, and very little traffic on the streets. The Mayor of Huaraz could do with making a visit here and taking some notes – the settings and sizes of the two towns are quite similar, but Old Huanky seems to do a far better job with traffic, rubbish and dogs.

This one’s for Anna. Vote….poo?

Time to fatten up, gorging on any cakes we can find. And to our delight, they are very easy to find. Our first rest day sees us downing copious amounts of alfajores, pañuelos, pinapple pastries, churros, cookies…and anything else the pastelerias will sell us for S/.1.

The cobbler in town seems to have done a good job…but only time will tell how it stands up to the strain of the next 700km section of our trip from Huancavelica to Abancay. Fortunately the Ortliebs are 4 years into their 5 year warranty period, so Lyon Equipment have sourced us a new set.

See our full Peru’s Great Divide: Part 2 photoset on Flickr.

[flickr_set id="72157636812490246"]